Short-necked vessel-making processes are, not surprisingly, very similar to processes used for making long-necked vessels. They are presented here as a separate category to clearly demonstrate—through the videos—that, although the tubular neck is not a major “architectural” feature of the finished object, it is still a key part of the Roman-period glassblowing process. In Chapter 5, we will take this point further: In creating some forms, like bowls and dishes, the tubular neck completely disappears during the later moments of the glassblowing process.

Two examples of full-size mold-blowing will also be demonstrated and discussed. Then, because they appear so frequently in Roman-period glass and are very interesting in terms of their manufacture, a variety of handle-making processes will be featured.

It is perhaps surprising that the cylindrical storage bottle (Fig. 46) was blown using a full-size blow-mold; its simple shape could easily have been created by free-blowing. The use of a mold is revealed by the slight bulge of the lower shoulder, where the glass inflated outward slightly beyond the confines of the mold’s upper edge. Although often barely visible, this is a common feature in large storage jars of the Roman period (Fig. 47). Using a mold would have made it easier and quicker to make vessels with the same diameter and approximately the same height. Consequently, they would have had similar capacities, an asset in storage vessels (Vid. 30).

In this square bottle (Fig. 48), the use of the mold is obvious. Characteristic of many storage vessels is the massive, slightly downturned folded edge at the opening. The shape and thickness make it almost indestructible—for glass (Vid. 31).

Large lidded vessels like this example (Fig. 49) were probably made for storing goods. However, many—if not most—have been found intact within sarcophagi in excavated ancient cemeteries. Along with other grave goods, the glass vessels contain the cremated remains of the deceased.

The process of making the lid is particularly interesting in two respects. The lid begins simply as a long-necked vessel process that has been modified to create an opening where a flat base would otherwise be. The lid process ends with the object being held with a clamp-like device. This allows the finial decoration to be made and avoids an unsightly punty mark that would mar the appearance of the lid (Vid. 32).

It may seem odd to devote an entire portion of a chapter to handles alone. I do this because, in terms of both their design and the processes by which they were made, Roman-period handles are much more interesting than they look.

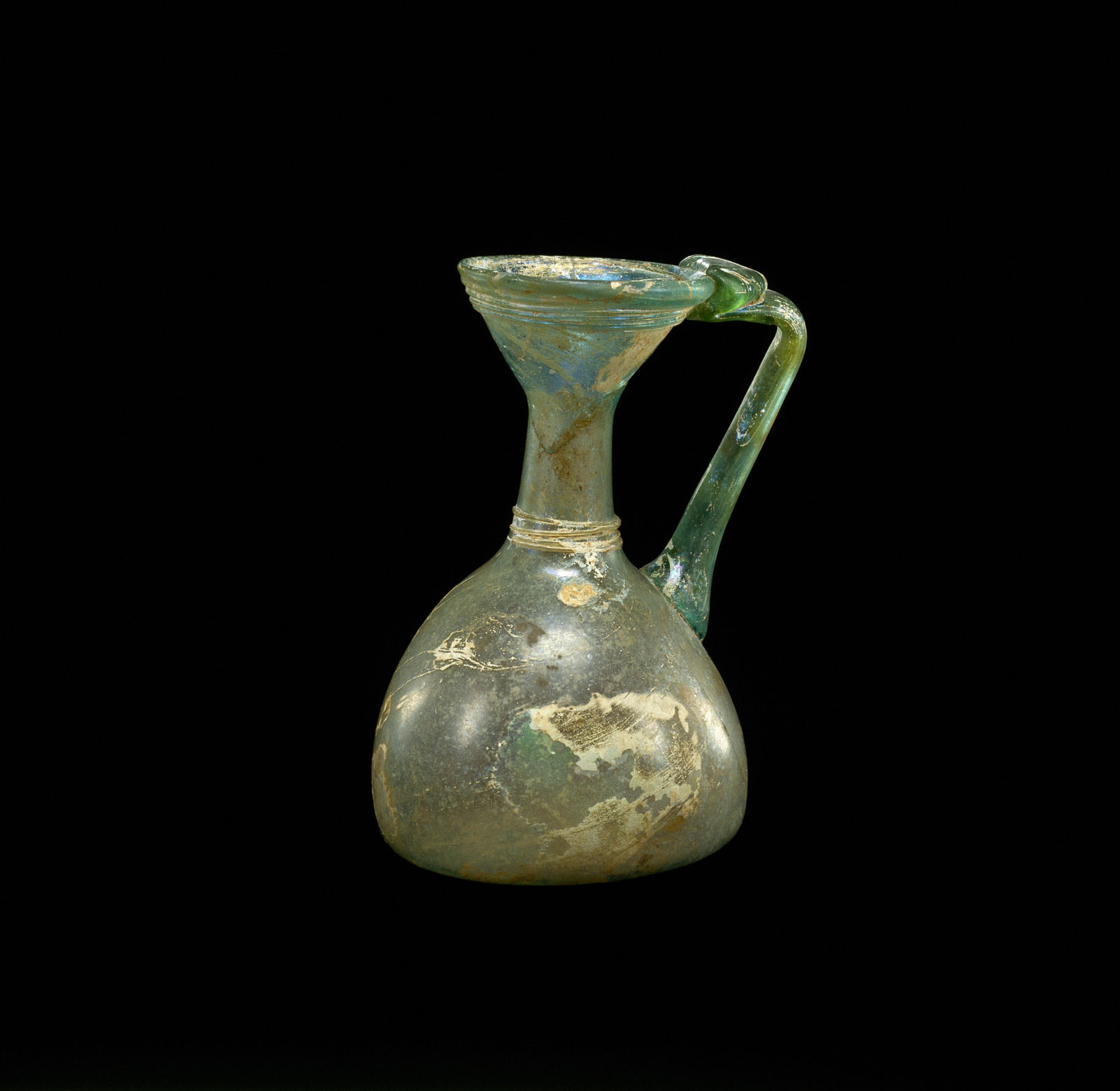

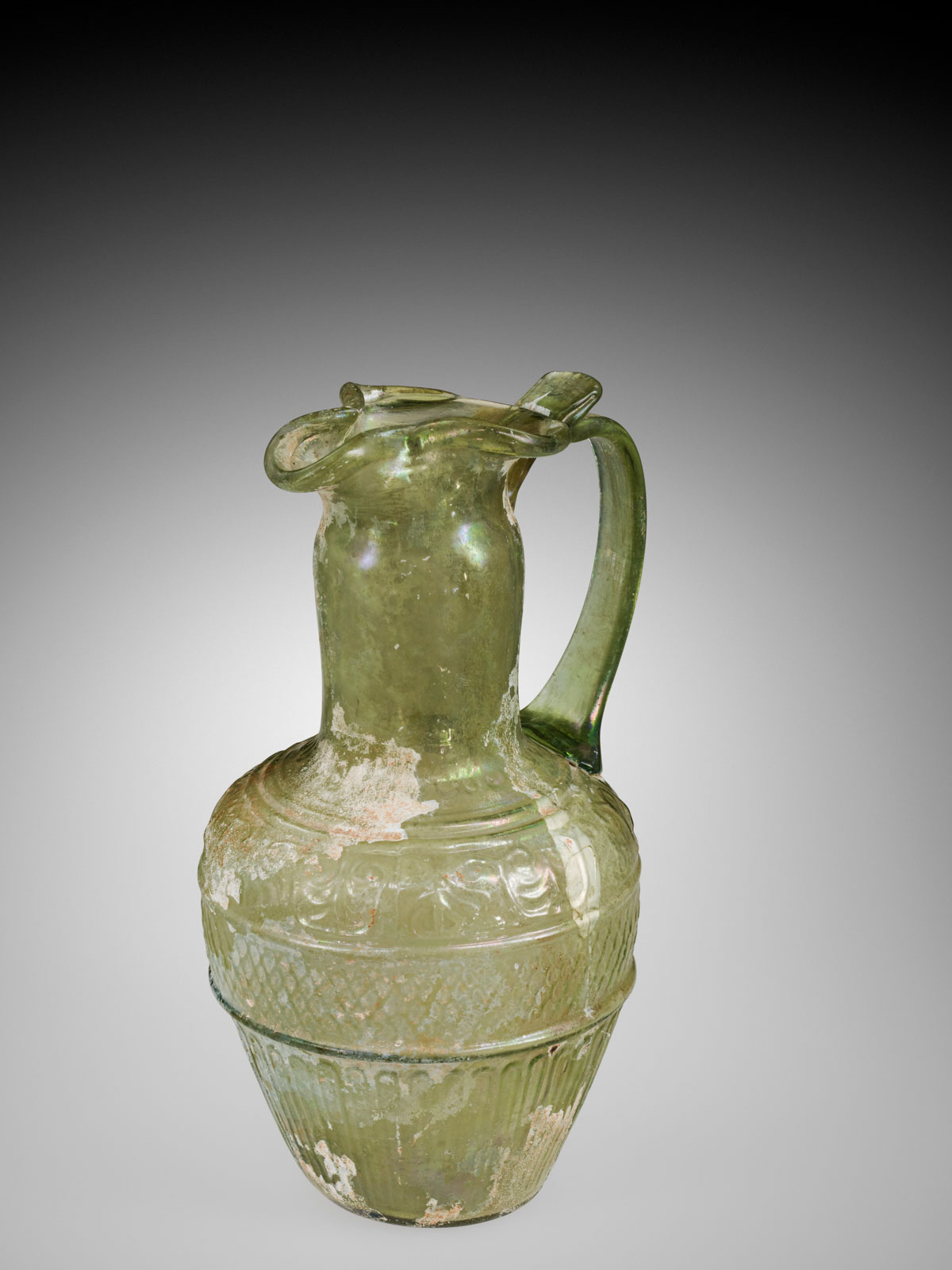

If one surveys many handles from, say, the first four centuries A.D., a number of common characteristics begin to stand out. First, they are rarely round in cross section (Fig. 50.1, Fig. 50.2, Fig. 50.3, Vid. 33). Most often, they are rectangular in cross-section, that is, band-shaped (Fig. 51.1, Fig. 51.1, Vid. 34). Many have one, two, or many ribs on their outer surface, running from top to bottom (Fig. 52.1, Fig. 52.2, Fig. 52.3, Vid. 35).

There is an entirely practical reason for avoiding round handles: it makes the annealing process easier. Flattened handles, especially those with ribbing, can lose their heat more quickly than round handles. This is because they have more surface area for radiant and conductive heat loss. Because the handle is always the last, and consequently hottest, thing to be added to a vessel, it is essential for it to cool quickly in order to equalize the temperature of all parts of the object. The flat shape of the handle makes it less likely to crack upon cooling, and it also speeds production. (For a more thorough explanation of the annealing process, please see Chapter 3).

Second, nearly all Roman-period handles are “down-up” handles. That is, the first attachment point of the added glass is lower on the vessel than the second attachment point. This is the case in all of the handles shown above. “Up-down” handles are, by comparison, rare (Fig. 53.1, Fig. 53.2). In these two cases, the handles are added while the vessels are still attached to their blowpipes.

Third, Roman-period handles never have a shear mark revealing where the glass used for the handle was cut free from its gathering rod. Instead, after the second attachment point was made, the excess glass was “cast off.” This process can be seen in all of the videos above. Usually the “tail” of the cast-off glass at least partly disappears into the larger, hotter mass of the handle.

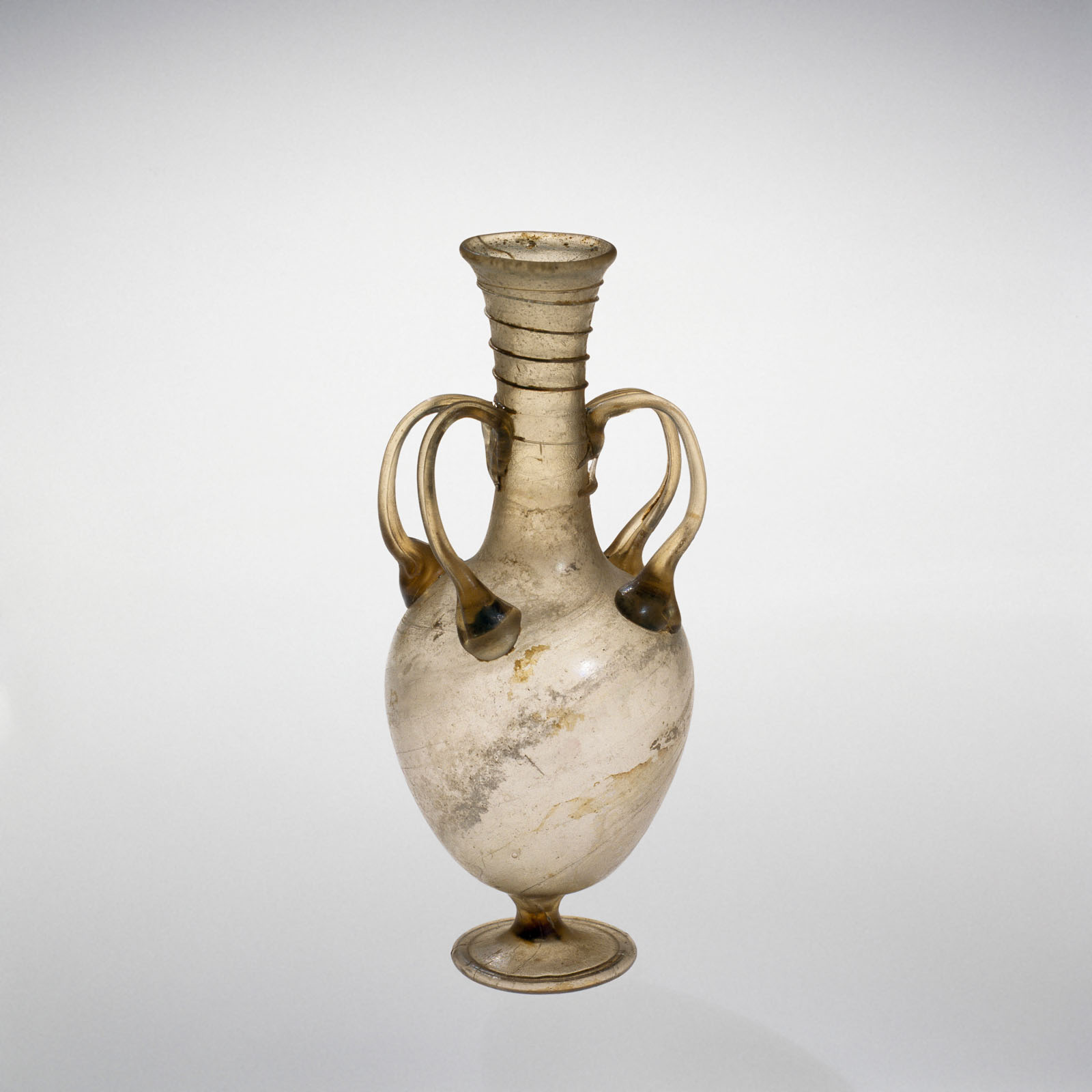

Roman-period handles sometimes show what appears to me to be playfulness. The double handle (Fig. 54, Vid. 36) and the vessels with 12 (or more!) handles look like good-natured études (Fig. 55, Vid. 37).

In general, handles seem to be an outlet for creativity and virtuosity. They were places where the ancient glassworkers could add a bit of personality and style to otherwise prosaic utilitarian objects that they were making by the hundreds, if not thousands.