The technical accomplishment of early glassblowers is, by itself, impressive. That so much ingenuity and creativity were also lavished on their work makes these craftsmen—laborers—all the more to be admired. Much surviving Roman-period blown glass evinces a strong and refined sense of design. To what extent the artisans who made these objects may have worked with designers, as we would term them today, we cannot say. But however this work was accomplished, Roman glass objects are often strikingly beautiful.

The objects in this chapter were chosen to illustrate a range of technical difficulty, from easy to very complicated, and from mundane to humorous. They are meant to show how one basic technique can be adapted to make a wide variety of products.

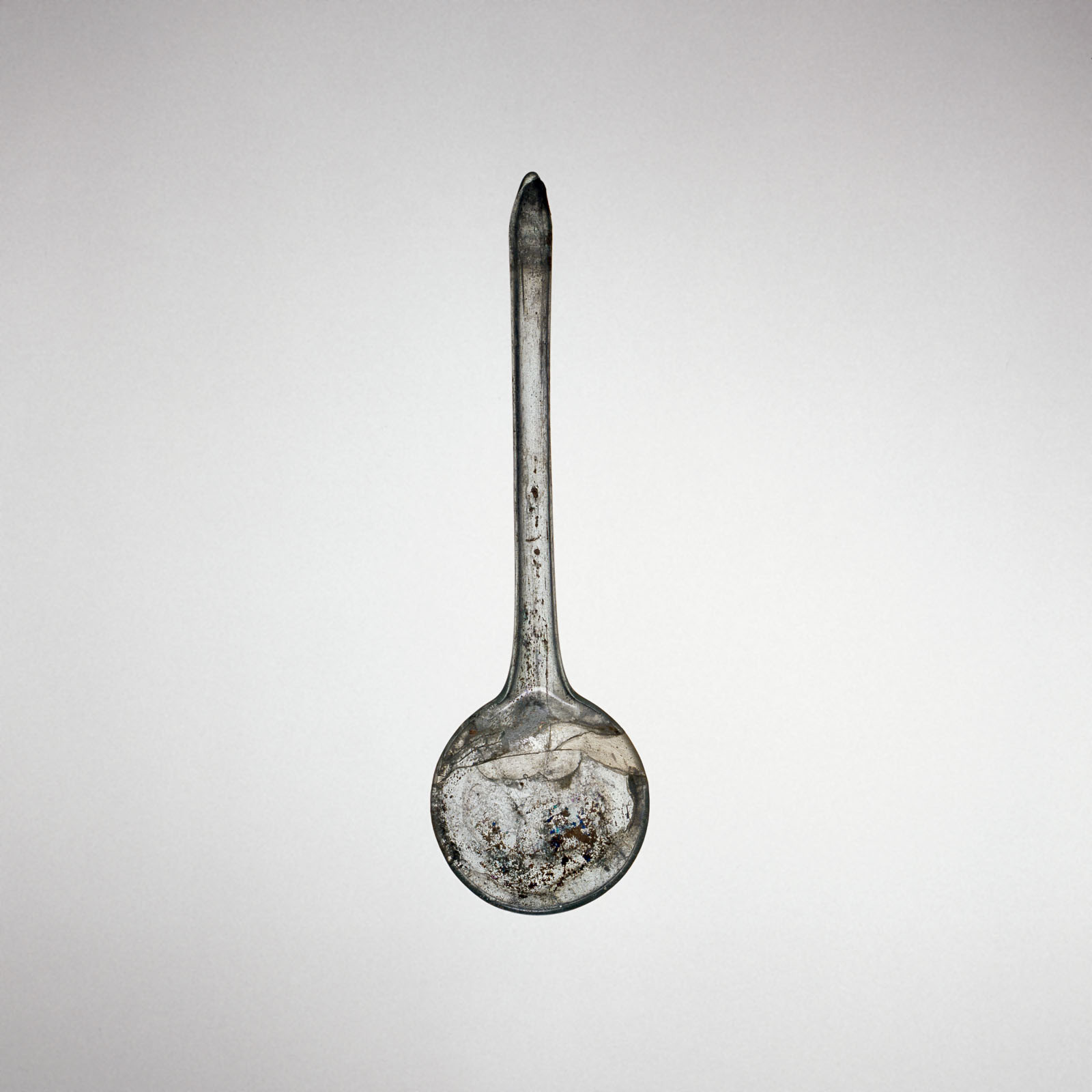

Of all the objects in this e-book, the spoon is the easiest to make (Fig. 40). Video 24 shows the making of glass tubing by a simple manipulating technique that does not involve inflation. Tubing can also be made by glassblowing. (Strictly speaking, this is not a long-necked vessel process, in that the tubing and the vessel’s body—the spoon portion—were made with separate procedures.)

The funnel’s tube was made entirely by mechanical force to pull a portion of the initial bubble until it was both long and narrow. The rim of the larger opening was created by the cracking-off process (Fig. 41, Vid. 25).

The elegantly shaped bottles in the form of birds that survive from the first century were made with a combination of furnace working and flameworking (Fig. 42, Vid. 26).

The next two objects arguably qualify as informal sculpture as much as utilitarian objects (Fig. 43, Vid. 27, and Fig. 44, Vid. 28). It should be noted that they are hollow and relatively thin-walled rather than solid. Interestingly, at the time these were made, it would have been nearly impossible to make them of solid glass. There was certainly sufficient skill on the part of the worker to do so, but a nearly insurmountable problem would have been encountered. Safely cooling solid objects of this size, shape, and varied thickness would have required a carefully and closely controlled process for a long period of time, possibly as long as a day. Today, the process is called annealing. This problem warrants a thorough explanation because it applies to all glass objects made by hot-working processes.

Glass, like most other materials, expands (gains volume) as it is heated; conversely, it shrinks as it is cooled. After any hot-working process—casting, kiln working, glassblowing, etc.—the glass is allowed to cool to the point of stiffness, at roughly 1,000 degrees Fahrenheit (540 degrees Celsius), so that it will maintain its shape. As the temperature of the object begins to decrease to room temperature, it is essential that the thickest and thinnest parts lose heat at about the same rate. Otherwise, stresses will develop that will crack the object. To accomplish this requires a gradual and constant reduction in temperature over a period of time.

Here is where the problem occurs: The thicker an object, the more gradually—and the longer the period of time—it must be cooled. For work that is, say, two inches (3 cm) thick, this requires many hours of carefully controlled temperatures.

Glassworkers use specialized ovens specifically to carry out this process of gradual cooling, or annealing. Today, annealing ovens are typically heated by electric elements that are controlled by a computer. The proper annealing of a large sculpture by Stanislav Libenský and Jaroslava Brychtová, for example, might require months in the annealing oven. It is difficult to imagine wood-fired annealing ovens having the precision required to safely cool objects of any great thickness.

The new technology of glassblowing effectively also opened the door to larger objects of a more sculpted nature than had been possible previously.

On the other hand, a relatively large object that is made by glassblowing is hollow. Because no part is much thicker than any other, the object can be annealed much more quickly than if it were large and solid. Therefore, the new technology of glassblowing effectively also opened the door to larger objects of a more sculpted nature than had been possible previously.

The dropper flask in the shape of a helmet includes “snake-thread” decoration. Although this type of decoration was finely detailed and small, it was carried out entirely at the furnace (Fig. 45, Vid. 29).