Long-necked vessels, large and small, have survived in great numbers to the present day. In my experience, they often densely populate Roman-period glass collections, both public and private. They are countless and, frankly, seldom have much aesthetic appeal.1 However, because of their many variations and their wide range of decoration, long-necked vessels can nevertheless be very interesting from a purely technical standpoint. This is partly because, from whatever century in the Roman era they date, all long tubular necks serve as a reminder of their original function: they facilitated the separation of the hardened but still hot inflated glass from the blowpipe. For early craftsmen, they were an essential structural element of the glassblowing process (see Chapter 1).

The first six key objects in this chapter and their accompanying videos focus on different methods of forming the long neck and different ways of holding the object from the base to allow the open end to be reheated and given its final shape.

The first small bottle (Fig. 23) to be considered has a tubular neck formed by holding the bubble down to elongate it by gravity, and then to elongate it further by pulling it outward at the base of the neck with jacks. The latter part of this process is evident from both the slight constriction at the base of the neck and its accompanying toolmarks. To reheat the opening and complete the open end, the vessel was held by attaching it to the glass left on the end of the blowpipe (this is known as the moil). The resulting rough circular scar left on the base is often called an annular-ring punty mark Vid. 8.

The candlestick unguentarium (Fig. 24) has a long conical neck with a substantial constriction between the neck and the body of the vessel. In this type of vessel, there are usually coarse toolmarks on the narrowest part of the constriction. Here, unlike the previous object, the long neck was created entirely with the mechanical force of pulling outward. This was done first when the bubble was on the blowpipe, and thereafter when the object was being held from its base. Like the previous object, it too was “puntied” to the moil to be completed (Vid. 9).

The next example (Fig. 25) is among the large number of blown glass vessels made entirely by hand that have the most common type of punty mark: a rough, dot-shaped scar at the center of the base. All of them were created in a fashion similar to that shown in Video 10.

Many early long-necked vessels (Fig. 26) have a furnace-finished rim (here with a rim that is folded inward) but no punty mark. To permit the completion of the open end, these vessels were held from the base with a preheated clamp device. Sometimes this tool is called a snap or gadget. In the video, a modern tool commonly used by flameworkers is shown. There is little doubt, however, that much simpler, spring-loaded tools were employed in antiquity. Dents made by such tools can be seen on the lower portions of a small number of ancient vessels. This example also shows the most common decoration found in ancient blown glass objects: threading Video 11.

A great number of long-necked bottles similar to this example (Fig. 27) survive from the third and fourth centuries. They have a cracked-off rim and no punty mark on the base. While they are usually undecorated, this one has subtle cold-worked horizontal grooves. Such bottles can be very attractive in their simplicity and elegant lines. A variant subgroup has a curious funnel-like opening that is slightly upturned just below the rim (Fig. 28).

The video shows three different methods for the cracking-off process, which may have been invented in the early first century. It played a key role in producing vessels that could be afforded by nearly everyone. The first method is modern and requires a type of heat source that certainly was not available in the ancient world. The second method involves the use of a hot metal ring, which has shown great promise in my efforts to rediscover the methods probably used by Roman-period workers.

I developed the third method recently. It employs a hot conical tool that simultaneously scratches the glass and delivers the greatest amount of heat precisely where it is most effective. This method also answers a question I have long wondered about: Why do so many cracked-off rims have an oblique surface? That is, why is the cracked-off surface noticeably conical, and why is the inner edge always lower than the outer edge? This can be seen clearly in the example from The Metropolitan Museum of Art above (Vid. 12).

Experimentally, this effect can be re-created with great consistency if the geometry of the upper end of the blank has a small bulge near the top (as is shown in the video) and the hot conical tool is used for the cracking-off process (Vid. 12). The conical shape of the tool accommodates a considerable range of diameters of the bulge. Although glass works well and has the advantage that its size can be changed easily, I suspect that such a tool would have been made of metal. The cracking-off process is essential for much high-volume production work such as glassblowing—especially full-size mold-blowing—and is employed worldwide today.

Long-necked vessels can be altered in a multitude of ways. Some alterations are structural and can change a vessel’s function, and some are simply decorative. The next 11 objects and their accompanying videos show a selection of both categories of alterations.

The feature often termed a “Roman foot” is a ring-shaped fold in the inflated glass that forms a stable, strong, and attractive base (Fig. 29). With few exceptions, a large, round pocket of air is trapped in the process (Vid. 13). The three feet seen in the Metropolitan Museum example (Fig. 30) are formed during the blowing and shaping of the vessel’s body. The high degree of difficulty of this procedure may explain why there are so few examples (Vid. 14).

Based on ancient accounts contemporaneous with its origin, this bottle (Fig. 31) is assumed to have been intended for use in feeding infants. Video 15 shows two different methods of forming the spout.

When soft glass attached to the end of a blowpipe or punty is held downward, it will be elongated by the force of gravity. Under the right circumstances, this can be used to create a decorative, drapery-like folding effect (Fig. 32). In this object’s accompanying video, this occurs on the blowpipe (Vid. 16). Later, in Chapter 5 (see “Handkerchief Bowl”), we will see the effect of this procedure with the object attached to the punty.

Pincers with a waffle-patterned working surface can be used during the blowing process to create decorative ribs (Fig. 33). This object, one of the many variants of “dropper flasks,” has an internal constriction at the base of the neck (Vid. 17). (It is difficult to see from the side and best viewed from above.) Another dropper flask can be seen in Chapter 3 (see “Dropper Flask Shaped like a Helmet,” (Vid. 29).

Optic molding (often called dip molding) is a decorative technique that usually (there are other patterns that can be found in glass of other periods) creates a pattern of ribs in the glass. More often than not, the pattern is twisted (Fig. 34). A thick-walled bubble of glass is lowered into the mold and briefly blown forcefully. The glass is then inflated further and given its final form (Vid. 18). The two terms are used interchangeably. “Optic” refers to the optical effect achieved. “Dip” refers to the fact that a glassblower only briefly dips the bubble in the mold so that the glass remains soft enough to allow the subsequent work to be carried out. Since its invention during the Roman period, the technique has seldom left the glassblower’s repertoire of decorative effects. For example, dip molding in its many varieties was widely used in Renaissance Venetian workshops (see renvenetian.cmog.org).

More of a curiosity than a technique ever used widely, the making of internal threads within the body of a long-necked vessel creates a weblike appearance (Fig. 35, Vid. 19).

Trailing (often called threading when the diameter of the added glass is particularly small) is a process of drawing out a long, narrow “cable” of glass onto the side of a vessel. The effect is sometimes structural, as when it is used to create a base. Often, trails are simply decorative.

Here Fig. 36, a base-ring is made from a spiral cable Vid. 20.

In this case, the base-ring is only one circle of cable (Fig. 37, Vid. 21).

The most common decoration on long-necked vessels is threading; the end result of threading is often called a wrap. Wraps can be placed around the vessel’s body or around the neck (Fig. 38, Vid. 22).

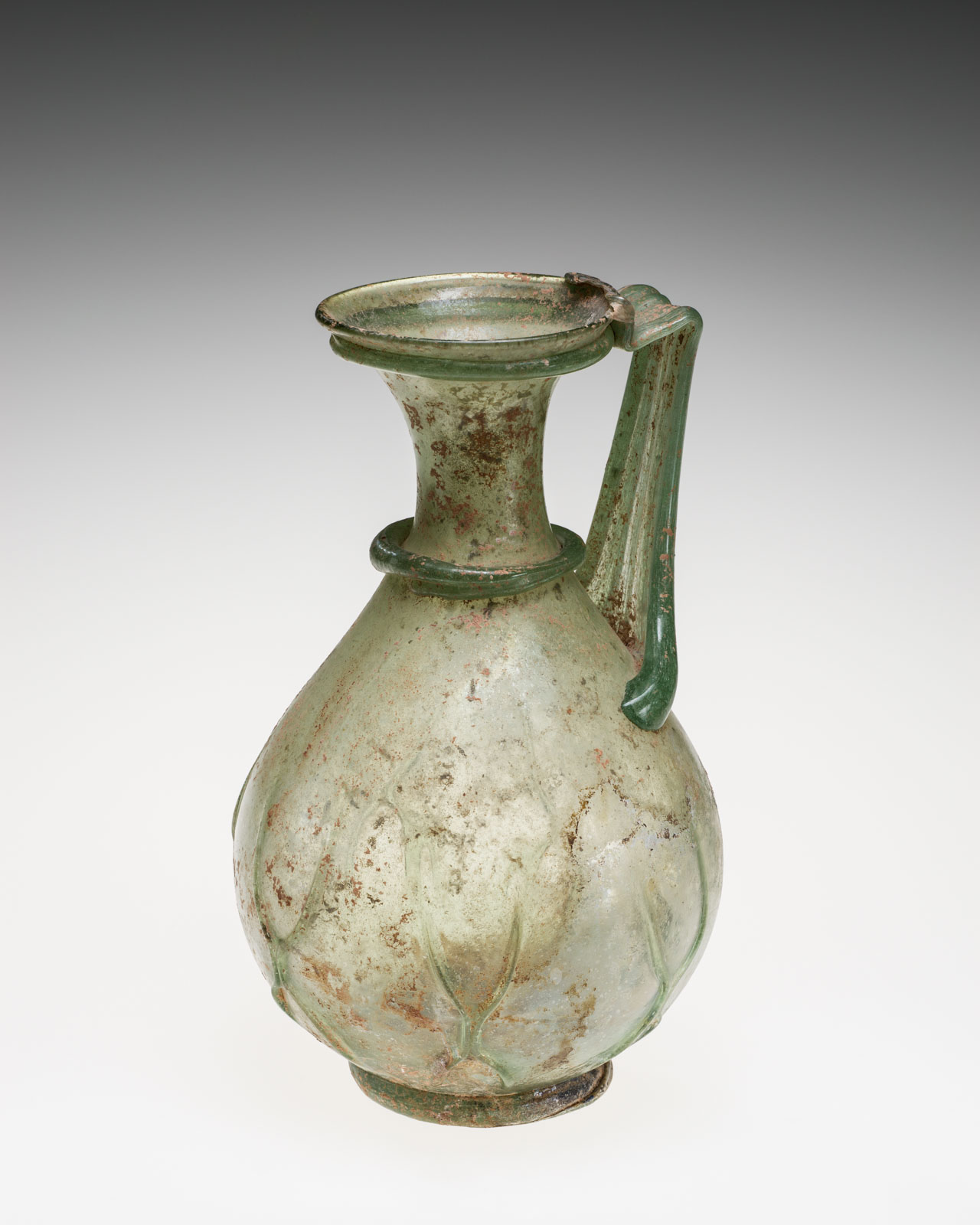

This elegantly formed pitcher has a functional base-ring and a single decorative wrap below the rim. Both have been pincered to create a denticulate pattern of decoration (Fig. 39, Vid. 23).

Long-necked vessels such as those described above can be made in as little as under two minutes. A decorative spiral wrap and a handle might add another two minutes of work time. Humble as these objects are, they are witnesses to the virtuosity and inventiveness of early Roman-period glassworkers.

Notes

-

David Whitehouse, Roman Glass in The Corning Museum of Glass, v. 1, Corning: the museum, pp. 123–160, cat. nos. 190–277. ↩︎