This e-book is about the discovery of a fundamental principle and the inventions of processes based on that principle. Together, they gave birth to a technological revolution. The discovery was that molten glass can be inflated. The inventions produced reliable processes from which useful, often beautiful objects could be made by inflation: glassblowing.

Since its beginnings, rapid development, and widespread dissemination, from about 40 B.C. through the first century A.D., blowing has been the dominant manufacturing method of glass. It is a technology that, in countless ways, continues to touch our lives every day, some 2,000 years later. Because glassblowing took root and spread within the Roman world, glass of the Roman period warrants our close study.

Glassblowing is a technology that, in countless ways, continues to touch our lives every day.

The general subject of Roman-period glassworking technology is vast. Glassblowing is but one of many hotworking processes used at that time for forming and decorating glass. A survey of some others, outside the limited scope of this publication, should be mentioned to put the “newness” of early glassblowing processes in better perspective. It will also make clear why the title of this work ends with the word ‘glassblowing’, not ‘glassworking’.

Let us begin with a big-picture view of glass manufacturing. Glassworking processes fall into one of two broad categories: cold working and hot working.

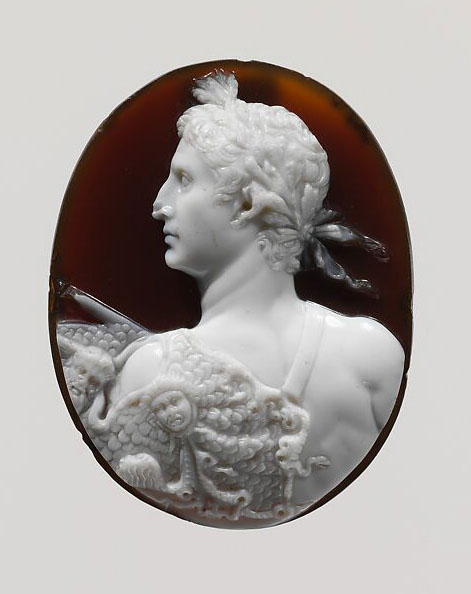

Cold working is always a reductive process in which material is removed. As the term indicates, this is done when the glass is at room temperature. The technology—often called lapidary work—long predates glass made by people. For example, prehistoric arrowheads and knife blades made of obsidian (a naturally-occurring glass) were fashioned by knapping, a cold-working process similar to chipping (Fig. 1). Sophisticated wheel cutting and engraving of minerals were used to make cylinder seals in ancient Mesopotamia (Fig. 2). During the Roman period, lapidary workers made gems and plaques from multilayered hardstones (Fig. 3).

Roman-period workers also made extensive use of cold-working processes to create form, to complete objects made by casting (for example), and to decorate objects by cutting facets (Fig. 4) and other patterns and by engraving representational images into the surface of objects (Fig. 5).

Aside from the crude cold working required to make cracked-off rims safe for use (Vid. 6) and a brief video segment showing how cameo blanks were wheel-cut to become beautiful gemlike objects (Fig. 7 and Vid. 4), cold working is not covered here.

Hot-working processes exploit the plastic state that glass assumes when it has been heated to a sufficiently high temperature: roughly 1,100–2,100 degrees Fahrenheit (600–1,150 degrees Celsius) for typical soda-lime glass of the Roman period.

Casting processes and various kiln-working processes such as fusing and slumping (with and without manipulative intervention by the craftsperson) were used to make products as disparate as ribbed bowls (Fig. 8)1 and ribbon bowls (Fig. 9)2. Neither technique falls within the scope of this publication.

Flameworking (often called lampworking) is a hot-working process in which a flame is directed at a piece of glass for the purpose of creating form and decoration3. (Flameworking is sometimes subtly distinct from furnace working, in which, often during manufacture, the entire object is positioned within the furnace.) In this e-book, flameworking makes only two appearances: during the forming of a bulge at the end of a preformed glass tube (Vid. 3) and during the completion of a first-century bird-shaped vessel (Vid. 26).

With the rarest exceptions, I suspect, Roman-period glassblowing took place at a furnace containing clay pots (or crucibles) of molten glass. The glass was collected (gathered) at the hot end of metal tubes and solid rods called blowpipes and punties (or pontils). This is the working method shown in the videos contained in this publication.

Furnace glassblowing—any glassblowing, in fact—can be divided into two broad categories. In free-blowing, the craftsperson uses gravity, centripetal force, and the simplest of tools to create objects (Fig. 10, Vid. 38). By sharp contrast, in full-size mold-blowing, a partly inflated bubble of glass is lowered into a mold, then further inflated to fully occupy the mold. Nearly instantly, the glass object is given its final size, form, and decoration (Fig. 11, Vid. 7).

This technique was probably invented in the early decades of the first century, and it was widely used thereafter. Its importance cannot be overstated: Essentially all glassblowing carried out on an industrial scale in the last 150 years has been done by full-size mold-blowing, the alternative to the much more skill- and labor-intensive free-blowing.

This e-book is the product of one person’s hands-on, reverse-engineered, investigative efforts into early glassblowing practices. I believe that my video-illustrated “reconstructions” provide credible answers to a question that can never be definitively answered: How, exactly, were these early blown-glass vessels made? To be clear, my videos respond to that question from this position: This is currently my best estimation as to approximately how these vessels may have been made. May, of course, is a critical word. In both principle and practice, similar results can often be achieved by somewhat different means.

I believe that my video-illustrated “reconstructions” provide credible answers to a question that can never be definitively answered: How, exactly, were these early blown glass vessels made?

My research method is straightforward. First, I closely study an object—preferably hands-on—trying to glean information (symptoms) that might illuminate the manufacturing process. This information can include variations in the wall thickness, distortions of bubbles trapped within the glass (thankfully, no ancient glass is free of bubbles), or toolmarks in telling locations, for example.

Next, I hypothesize a process (and alternatives) that is then tested at the furnace. After comparing my results with the original object, I make adjustments. In some particularly difficult cases, this pattern of hypothesizing, experimenting, and assessing can go on (intermittently) for years. Eventually, a reliable process emerges. Again, my videos indicate how a particular object may have been made.

Concerning questions of historical-period working practice, as can be seen in the videos, I work at a modern forced-air and methane-fired furnace, melt a soft (long-working-period) and nearly colorless soda-lime glass, sit at a modern-period glassworker’s bench, and use simple tools that may or may not closely resemble those of the Roman period. The very modern rubber blowing hose replaces an assistant blowing into the blowpipe (as needed) while I work on the glass with tools. Lastly, I work solo. In later times, we know from period illustrations that furnace glassblowing was carried out with at least one and often two assistants.

It would be reasonable to ask why I tolerate such a blatant lack of verisimilitude instead of making a more genuine effort toward authenticity. Over the last 20 or so years, I have worked many times at wood-fired furnaces, using decidedly stiff (short working time) glass, and seated with boards atop my thighs in place of the arms of a later-style glassblower’s bench (Fig. 12). From this experience, I have concluded that the convenience of my modern workshop outweighs the benefits of a more authentic working environment. However, I firmly believe that what takes place on the end of my blowpipe or punty would be entirely familiar to a Roman-period worker, were one to miraculously appear at one of my video-taping sessions.

Lastly, this e-book was conceived as a companion to three publications. It is meant to give an in-depth background to both of my earlier e-books: The Techniques of Renaissance Venetian Glassworking and The Techniques of Renaissance Venetian-Style Glassworking. This is particularly true of the chapter “Glassblowing before Its Arrival in Venice” in the first of these publications.

This e-book is also intended to complement David Whitehouse’s three-volume catalog Roman Glass in The Corning Museum of Glass, published between 1997 and 2003. (The descriptor “(Cat. 00)” immediately after a Corning Museum accession number refers to that publication.) All but three of the objects chosen as subjects for videos are in the Corning collection. It has been my goal to make a selection of objects that will represent as many as possible of the techniques practiced during the early centuries of glassblowing.

Notes

-

On the question of how ribbed bowls were likely made, Mark Taylor and David Hill of Andover, U.K., have exceeded all other efforts. At present, the best summary of their work can be found at http://www.theglassmakers.co.uk/archiveromanglassmakers/poster03.htm. ↩︎

-

A process similar to that used to make this ribbon bowl can be seen in William Gudenrath, “Techniques of Glassmaking and Decoration,” in Five Thousand Years of Glass, ed. Hugh Tait, London: British Museum Press, 1991, pp. 213–241, esp. pp. 219–221. ↩︎

-

See Gudenrath, p. 216. ↩︎